What is informed consent?

Informed consent is the process by which a treating health care provider discloses appropriate information to a competent patient so that the patient may make a voluntary choice to accept or refuse treatment [1]. It originates from the legal and ethical right the patient has to direct what happens to their body and from the ethical duty of the physician to involve the patient in their health care.

By dictionary definition, informed consent is:

permission granted in the knowledge of the possible consequences, typically that which is given by a patient to a doctor for treatment with full knowledge of the possible risks and benefits.

In medicine, in cases where there are more serious potential risks, patients may be asked to agree in writing to a practitioner’s plan for their care. This agreement in writing is part of informed consent, as it acknowledges a patient’s need to know about a medical procedure or treatment before they decide whether to accept or have it.

The elements of a full informed consent policy include:

- The nature of the decision/procedure

- Reasonable alternatives to the proposed intervention

- The relevant risks, benefits, and uncertainties related to each alternative

- Assessment of patient understanding

- The acceptance of the intervention by the patient

Most states (in the US) have legislation or legal cases that determine the required standard for informed consent.

In this short (1:11) video, benzodiazepine activist Heather discusses the concept of informed consent as it applies to benzodiazepines:

Click on CC for captions in English. To contribute translations of this video in another language, click here.

Why do we want informed consent for benzodiazepines and what would it look like?

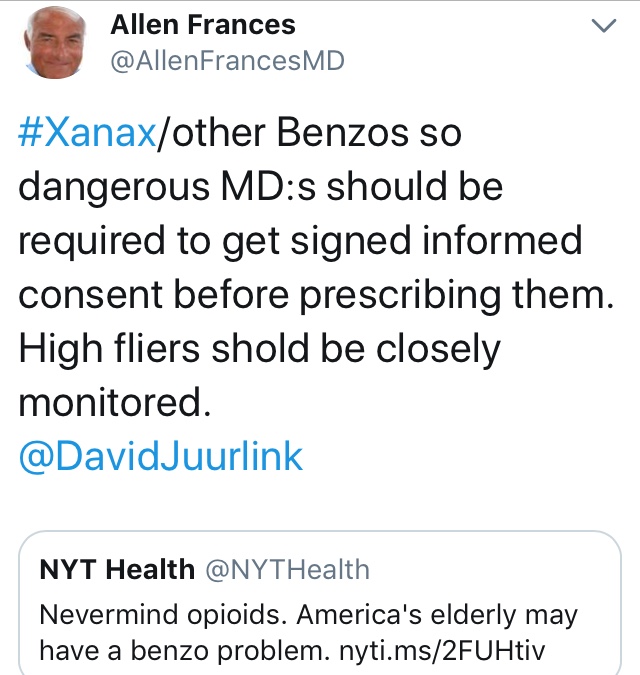

It should be acknowledged that policy and government involvement in medical matters can be controversial. Anecdotally, from self-reporting by victims of benzodiazepines in the support communities, there are numerous reports that individuals who have been injured by taken-as-prescribed benzodiazepine prescription were not given informed consent by their prescribers. They didn’t know this could happen to them. As a result, patients are harmed and they feel rightfully angry and betrayed by their medical providers, people who were supposed to help them. They feel they should have been given up-front all of the information about the risks and dangers regarding long-term use of benzodiazepines before they were prescribed the drugs.

Regardless of why this lack of informed consent is happening (lack of education on the part of medical professionals or a general attitude that benzodiazepines are “safe” or “harmless” drugs, etc.), it is clear that this needs to change and that patients have a right to informed consent. Many patients who were harmed by benzodiazepines state, after having taken them long-term and becoming unwittingly and unknowingly physically dependent, that they would never have agreed to take the medication long-term had they been informed about the risks and dangers of doing so beforehand. Would-be consumers of benzodiazepines have a right to this fair warning and information if medical providers are going to blatantly ignore the prescribing guidelines and warnings (given not only by numerous agencies and regulatory bodies but also by the drug manufacturers themselves) that benzodiazepines should only be prescribed for short-term (2-4 weeks, including tapering off time) use.

Some examples of important information that should be disclosed in the process of providing informed consent for new patients being offered a benzodiazepine and/or Z-drug prescription:

- The patient should be informed that they are being prescribed a benzodiazepine, which is a minor tranquilizer, which is a drug in the same class as Valium (diazepam).

- These drugs are recommended by the manufacturer (and numerous other professional and regulatory bodies) to be taken intermittently (not regular or daily use) or, when taken regularly, for no longer than a successive 2-4 week time period (including the tapering off period).

- Long-term use may worsen anxiety and panic (due to tolerance) and hinder recovery from these conditions in the long run.

- Taken any longer than 2-4 weeks, even as directed without abuse, these drugs can cause tolerance, interdose withdrawal, physical dependence and subsequent withdrawal syndromes, including the protracted withdrawal syndrome from benzodiazepines, which can last years.

- The withdrawal syndromes can be debilitating, severe, and are said to sometimes be worse than heroin withdrawal. Sudden cessation after long-term can cause seizures, suicide, and even death.

- Cessation of the benzodiazepine after long-term use requires a slow and controlled taper that can take many months or years to complete because that’s how long it takes the down-regulated GABA receptors to heal in withdrawal-susceptible individuals.

- Additive effects may occur with patients taking other depressant drugs such as alcohol or sedative antidepressants. A combination of opiates and benzodiazepines can prove deadly. W-BAD Note: antidepressants such as SSRIs or SNRIs may be stimulating to the fragile CNS in benzo withdrawal and recovery. Use caution when considering other medications.

- Elderly individuals should be warned that, due to decreased metabolism, they may be at risk for an increased susceptibility to the sedative effects of benzodiazepines which may cause mental confusion, cognitive impairment suggesting dementia and ataxia leading to falls and fractures.

- In pregnancy, there is a risk of adverse effects on the fetus, neonatal depression (floppy infant syndrome) and neonatal withdrawal effects.

- There are genetic differences from person to person in drug metabolism. Neuropsychiatric pharmacogenomic testing is available to determine how you metabolize benzodiazepines prior to being prescribed them.

- The patient should be warned about the risks of ingesting a fluoroquinolone antibiotic while taking benzodiazepines.

- Benzodiazepines may be implicated in an increased risk of dementia and other health issues, illness, and morbidity.

Examples:

1. The ‘benzodiazepine bill’ (H.3594) in Massachusetts calls for informed consent in the following ways:

In filling a prescription for a benzodiazepine or a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic prescription, the pharmacist shall ensure that the label includes a cautionary statement explaining the risks associated with long-term use which shall be bolded and contained within a box.

and

No practitioner shall prescribe a benzodiazepine or a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic, as defined in section 1 of chapter 94C, without first obtaining the patient’s written informed consent. The commissioner of public health shall prescribe a form for physicians to use in obtaining such consent. This form shall be written in a manner designed to permit a person unfamiliar with medical terminology to understand its purpose and content, and shall include the following information: (i) misuse and abuse by adults and children; (ii) risk of dependency and addiction; and (iii) risks associated with long-term use of the drugs.

2. Two Sample Benzodiazepine Informed Consent Forms:

Both of the following informed consent forms for long-term prescription of benzodiazepines are a good start however, they seem to minimize (or fail to disclose) the potential severity of the withdrawal syndromes which may occur. One also implies that SSRIs are “safer” than benzodiazepines, which studies show is not necessarily true.

Informed Consent for Benzodiazepines for Anxiety Disorders

Informed Consent for Chronic Benzodiazepines

Sources:

[1] Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patient’s competence to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007; 357: 1834-1840.

Further Reading:

‘What is Informed Consent?’ by benzoinfo.com

A Model Consent Form for Psychiatric Drug Treatment