Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome from therapeutic use of benzodiazepines is a physical problem, not an addiction problem.

Making the distinction between addiction and dependence is important because the two issues are treated differently medically.

For example, one wouldn’t treat an infant for addiction/drug abuse if the infant were born with a physical dependence.

Put simply, addiction features the behavior of drug abuse while physical dependence does not.

Most patients experiencing adverse effects and/or the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome are NOT addicts.

Why?

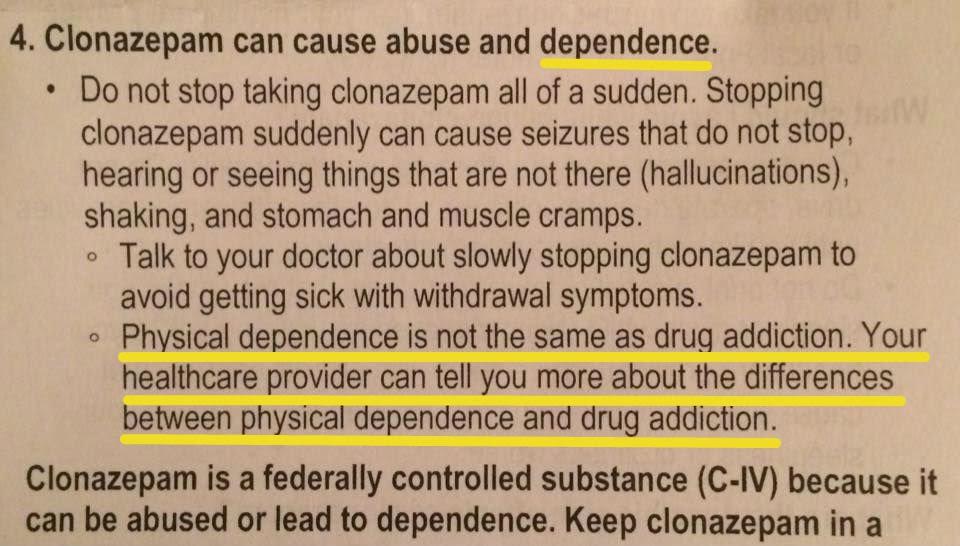

It is widely recognized in the existing medical literature that physical dependence can develop with the chronic use of many classes of medications. These include beta blockers, alpha-2 adrenergic agents, corticosteroids, proton pump inhibitors, antidepressants, and other drugs that are not associated with addictive “disorders.” While physical dependence and tolerance may be present in individuals with addiction (simply by way of taking the drug regularly), it is important to note that a person’s body may develop a physical or physiological dependence (and/or tolerance) to the presence of a chronically administered medication, without being an addict or having a substance abuse disorder. This phenomenon can happen to someone on heart medication or psychiatric medication, including benzodiazepines, when taken exactly as prescribed. The body’s acclimation to the chronic presence of the medication results in neuroadaptations and, ultimately, a dependency on the medication.

A percentage (~50-80% according to Reconnexion, although the existing estimates as to the exact percentage varies due to lack of studies) of people taking a benzodiazepine therapeutically/as directed, will develop a physical dependence and/or adverse effects, which may include tolerance and withdrawal symptoms between doses (interdose withdrawal) which can look like addiction, but it’s not. Until further research is conducted in managing the problem, the most widely accepted approach to reverse a physical prescribed dependence to benzodiazepines is a slow taper, sometimes incorporating diazepam substitution tapering, to minimize the risk of a severe—sometimes lasting years—withdrawal syndrome (protracted withdrawal, which can occur in up to 15% of benzodiazepine patients). Physical dependence can ensue even if the medication in question is within the generally accepted (licensed, prescribed dose, or “standard of practice”) dose range. Escalation is not common as it is with addiction. If there is dose escalation in a patient, it may be either recommended by the prescriber or, if done by the patient themselves, could be due to a phenomenon called “pseudoaddiction” in response to the suffering of interdose and tolerance withdrawal (which the patient may not even be aware they are suffering from, but instead feel they have “intolerable” or “increasing” anxiety and discomfort).

The importance of distinguishing dependency from addiction is profound, because addiction protocols and “detoxes,” especially in the U.S., are not typically safe nor are they effective for people who are merely dependent on a benzodiazepine without a substance abuse disorder. While dependency can co-exist with addiction making addiction treatment protocols helpful for the behavior of abuse in those patients, most people in benzodiazepine withdrawal and recovery do not have a substance abuse disorder, and therefore may be further harmed if the physical dependence is managed with the addiction model.

Why is this a problem?

- Patients who are not addicts are being treated for addiction – and that’s why addiction treatment doesn’t work for these patients.

- This common misunderstanding is a primary reason why the epidemic with benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome has gone on so long.

In the U.S., a consensus statement released by The American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine sought to define the terminology and recommended their definitions for use. The definitions presented in the consensus statement are as follows:

ADDICTION:

Addiction is a primary, chronic, neurobiological disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

PHYSICAL DEPENDENCE:

Physical dependence is a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

TOLERANCE:

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

The consensus statement goes on to explain the reasoning for defining and distinguishing the terms:

Physical dependence, tolerance and addiction are discrete and different phenomena that are often confused. Since their clinical implications and management differ markedly, it is important that uniform definitions, based on current scientific and clinical understanding, be established in order to promote better care of patients…

Clear terminology is necessary for effective communication regarding medical issues. Scientists, clinicians, regulators and the lay public use disparate definitions of terms related to addiction. These disparities contribute to a misunderstanding of the nature of addiction and the risk of addiction. Confusion…results in unnecessary suffering, economic burdens to society, and inappropriate adverse actions against patients and professionals.

Mind your language

To maximise our effectiveness for raising awareness about iatrogenic physical dependence, adverse effects, withdrawal syndromes and harms (associated with therapeutic use of benzodiazepines), it is advisable for to use the following language in our activism efforts.

See the Mind Your Language Page for important examples.

Further Reading

For more information on this important distinction, please visit:

- Mad in America: Don’t Harm Them Twice: When the Language Surrounding Benzodiazepines Adds Insult to Injury (Part I)

- Mad in America: Don’t Harm Them Twice (Part II): What Can Be Done?